Elderly care: Increasing outdoor usage in residential facilities

Well-designed outdoors environments can have a beneficial effect on the health of older adults in residential facilities by encouraging them to more spend time outdoors.

Susan Rodiek, PhD, NCARB & Chanam Lee, PhD, MLA

|

Figure 1: Walkways can encourage physical activity

|

The purpose of this study was to learn how the designed environment can encourage or discourage elderly residents from spending time outdoors in long-term care settings. The research was conducted at 68 randomly-selected assisted living facilities in three diverse climate regions of the US (Houston, Chicago and Seattle).

Residents and staff (N=1560) filled in written surveys on outdoor usage and preferences, with corresponding staff questions to confirm the validity of resident responses. The outdoor areas at each facility were evaluated with a 63-item environmental audit tool, testing seven core design principles derived from previous research and practical experience.

After controlling for factors such as gender and mobility, the study found several environmental features that significantly influenced how much time residents spent outdoors. Features associated with increased outdoor usage were: high accessibility, clear indoor-outdoor connections, safe paving, good maintenance, round-trip walkways and a choice of comfortable sitting areas with appealing views. There was strong correlation between outdoor usage, walking, physical activity, environmental satisfaction and self reported health of the residents surveyed.

The implications of this study are that welldesigned outdoor environments can have a major impact on health-related behaviour in long-term care settings, potentially leading to substantial therapeutic benefits. By better understanding specific features that promote outdoor usage, environmental designers may significantly impact the health and

well-being of a growing population of frail elderly residents.

|

Figure 2: Outdoor areas can provide places for activities

|

Well-designed outdoors environments can have a beneficial effect on the health of older adults in residential facilities by encouraging them to more spend time outdoors In a rapidly ageing global society with diminishing resources, it is increasingly important to find cost-effective ways to promote and maintain health in older adults.

Having access to nature and the outdoors is widely considered to be therapeutic for elderly residents in long-term care settings. Recently, research is beginning to confirm that older adults who spend time outdoors may derive health benefits such as better sleeping patterns, less pain, decreased urinary incontinence and verbal agitation, better recovery from disability, and even increased longevity1-4.

In spite of knowledge of potential health benefits, and although most residential care facilities provide usable outdoor space, it is commonly reported to be underused by elderly residents5-7. Relatively few studies have assessed how environmental design can encourage outdoor usage; however, a number of studies have examined how environmental features may encourage physical activity8,9.

Others have developed design guidelines to improve the usability of outdoor space, based on research, practice and theoretical underpinnings10-14. Components such as outdoor walkways, activity spaces and indoor-outdoor connections (Figures 1-4) are considered to be important for older adults. However, because of the scarcity of outcome based studies, the specific environmental features that encourage outdoor usage are not fully known.

|

| Figure 3: Easy indoor-outdoor connections help to encourage elderly residents to access outdoor space |

Methodology

The main objective of this research was to learn how the physical environment influences outdoor usage in long-term care settings, so future facilities can be designed to better support residents’ needs and preferences.

The main methodology reported in this paper compared residents’ levels of outdoor usage with assessed environmental qualities, after controlling for various personal and environmental factors.

This study focused on an intermediate level of residential care, typically called ‘assisted living’ in the US. This consists of relatively homelike congregate residential settings that provide a range of assistive services13. At the assisted living level, the majority of residents are still able to access the outdoors independently, but typically spend most of their time in the facility environment. Although people with advanced dementia are also reported to derive benefits from having outdoor access14-16, they were not included in the scope of this study.

The study was conducted in three of the 10 primary emerging megapolitan regions of the US17, selected on the basis of having the greatest climatic diversity18. In each region, the sample selection area consisted of a two hour driving diameter from the core of each region’s primary city: Houston, Texas; Chicago, Illinois; and Seattle, Washington.

Residential facilities were randomly selected from the list of all licensed assisted-living facilities with 50+ residents. This resulted in 68 facilities total, ranging from dense urban contexts to outlying urbanised suburbs and towns.

Written surveys were developed to assess outdoor usage, activities and preferences. Specific questions in the staff survey were used to verify and confirm the levels of outdoor usage reported by residents. The surveys were pre-tested and revised several times, with the final versions having 40+ closed-ended questions, plus additional write-in responses. In pre-testing, residents had difficulty calculating the overall amount of time they spent outdoors per week or month, so instead they were asked how often they usually went out and how long they usually stayed each time; their responses were multiplied to obtain the minutes per week they spent outdoors.

Residents and staff were recruited by written invitations distributed by facility administrators. Residents (N=1128) completed surveys independently, in small group sessions with assistance from researchers as needed. Staff (N=432) completed surveys independently and, in some cases, returned them by mail.

The mean age of residents was 83.9 years (range 33 to 104), with 79% women and 21% men. The mean age of staff was 44 (range 27 to 62), with 89% women and 11% men.

Residents were predominantly Caucasian, while staff race and ethnicity were fairly diverse; percentages roughly approximated the estimates for each sample population.

Environmental audit process

The outdoor areas at each facility were evaluated with a 63-item environmental audit tool, using a 10-point scale to rate each environmental feature or quality. A team of two trained researchers completed the environmental audits, using the same personnel at all facilities. Because most facilities had at least a few outdoor areas, researchers used observation, physical traces and staff reports to learn which outdoor areas were most used by residents. They evaluated a maximum of three outdoor areas at each facility, using printed audit forms. The two evaluators worked independently, and later their ratings for each item were averaged.

The audit tool developed for this study tested seven core design principles derived from a comparison of widely cited publications in the recent literature. Because of the scarcity of empirical research, the most comprehensive information on this topic was found in ‘best-practice’ design guidelines developed by experienced architects, landscape architects, gerontologists and care providers; these sources generally had high levels of agreement on the main environmental qualities considered to influence outdoor access for older adults, and were also generally in agreement with existing empirical studies on the topic.

To develop the hypotheses, the most commonly cited environmental issues were placed in a matrix and grouped into distinct categories, resulting in the following seven core principles to be tested in this study:

1. Indoor-outdoor connections: how well does the outdoor area connect with the common indoor areas and circulation routes?

2. Contact with the world beyond the facility: are residents able to view off-site features such as landscaped areas, roads or human activities?

3. Safety and security: is the outdoor area safe and secure, with good visual contact with the indoors and designed to minimise the risk of falling?

4. Comfort and accessibility: does the outdoor area comfortably support the physical needs and reduced functional abilities of older residents?

5. Freedom, choice and variety: does the outdoor area provide opportunities for stimulation, autonomy and personal choice?

6. Enjoyment of nature: does the outdoor area offer an abundance of appealing nature elements, presented in ways older adults could enjoy them?

7. Place for activity: does the outdoor area afford safe, comfortable, inviting opportunities for walking or other activities?

In order to test these principles in actual settings, specific environmental features were developed as items that could feasibly be rated. For example, a more accurate rating can be established for a door threshold than rating the overall ‘accessibility’ in an outdoor area. The evaluators were asked to rate each feature according to how well it would support

usage by elderly residents. Thus, instead of rating a door threshold as a physical object, it was rated according to how easily a resident could get across the threshold. Each of the seven core design principles was assessed with 8-10 individual features that appeared to be its main components, resulting in 63 total items. Each feature was rated from 1-10, with 1 being an ‘extremely poor example’, 5 being ‘average’ and 10 being ‘the best that could be expected’.

In pre-testing, the audit tool was found to have high inter-rater reliability (the level of agreement between different raters), with Cronbach’s alpha and intra-class correlation coefficients ranging from .92 to .95 for the overall scale (.70 is often considered adequate reliability). In addition to ratings, certain environmental features were measured directly, such as the presence or absence of an automatic door opener or the pounds of force needed to open a manually operated door.

|

Figure 4: Outdoor seating and gardens create a comfortable, welcoming environment

for less-mobile residents |

Analysis

Resident surveys without a full set of responses were dropped from the analysis. To account for the clustering in the data (e.g. residents from the same facility share the same environmental features), the Huber-White robust covariance estimator for clustered data was used in STATA. In addition, as several of the environmental variables had similar or overlapping characteristics, all items from each principle were analysed using factor analysis.

This grouped the correlated variables into distinct categories using a common latent factor variable. These latent factor variables were tested but did not lead to significant results, so individual audit items were analysed separately and only those items significant at the level of 0.10 were retained. Individual variables were examined for distribution and several variables were categorised or transformed to ensure proper distributions necessary for running statistical modelling.

To begin, the model included all possible variables of interest in a linear regression model and used a backwards stepwise approach. At each step, the variable with the highest p-value (the lowest statistical significance) was removed from the model (if two were close, the one of least interest was removed), until the significance levels of all the remaining regression coefficients were at most 0.10.

Aside from questions relating to the main outcomes, a number of personal variables were surveyed and tested for their significance in the model, including: gender, age, health, vision, history of falls, mobility, level of daily assistance needed, pet ownership, urban vs rural background, former occupation and attitudes and preferences about the outdoors. Variables found to be significant were controlled for in the analysis.

Because nearly all facilities were found to have at least 2-3 usable outdoor spaces (mean=2.24 outdoor spaces rated per facility), it was reasoned that the most-used spaces would exert the greatest influence on outdoor usage, while the less-used spaces would have relatively less impact. Therefore, in arriving at the overall ratings for each environmental variable at each facility, the ratings were weighted according to how much the different outdoor spaces were reported as being used by residents. Rather than combining separate items to achieve an average rating for each of the seven general principles, the rating for each of the 63 environmental variables was entered separately in the model.

Preliminary analysis found that most facilities had a few residents who spent far more time walking than other residents did. Verbal reports suggested that those with very high levels of walking might be motivated by pre-existing habits, interest in staying healthy, etc and less influenced by environmental conditions than the typical resident. Therefore, two models were constructed: a full model with all residents and a second model excluding the very ‘high-level walkers’ who walked more than 500 minutes per week.

Comparing outcomes, it was found that, although there were differences with and without the high-level walkers, the environmental relationships were fairly comparable overall. The model that excluded the high-level walkers showed stronger association with the environmental variables of interest, appeared to be somewhat more consistent and stable, and is reported in this paper, except where noted otherwise.

|

|

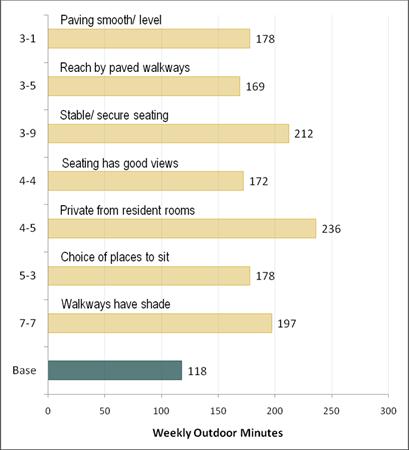

| Figure 5: Environmental features with the lowest impact |

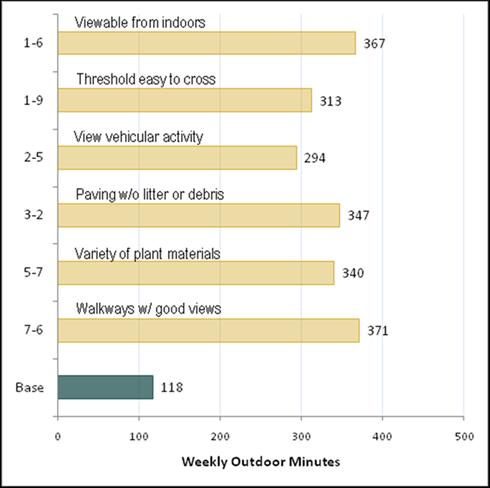

Figure 6: Environmental features that increased

outdoor usage by up to 3.5 times |

Results

In the model that excluded the high-level walkers, residents reported 241 minutes per week (mean) and 75 minutes per week (median) of time spent outdoors (about 20-60 minutes per day). The distribution was skewed, but roughly corresponded with staff estimates that residents spent 185 minutes per week outdoors (about 45 minutes per day) and helped confirm the resident self-reports.

Several non-environmental factors were found to be significant and were controlled for in the analysis. Age was inversely related to outdoor usage, so that older residents generally spent less time outdoors. People using assistive devices such as walkers or wheelchairs also spent less time outdoors.

Gender did not make a significant difference in outdoor usage, but people with pets spent considerably more time outdoors. People spending more time outdoors reported that they cared very much about being outdoors, they felt more free outdoors than indoors and they preferred to walk outdoors rather than indoors, when possible.

Surprisingly, people who spent more time outdoors were also more worried about falling outdoors; this might be due to being outside long enough to observe existing hazards and barriers.

Overall, this study found that several of the hypothesised environmental features, including some from each of the core design principles, were significantly associated with substantial increases in outdoor usage. In Figures 5-7, the bars on the graphs simulate (extrapolate) the increased minutes of outdoor usage per week, if that specific feature received a three-point higher than average rating on the audit scale (i.e. rated as eight out of 10 possible points), while all other significant environmental features were held at an ‘average’ rating of five points.

The ‘base’ outdoor usage if all features were rated at five points was found to be 118 minutes per week, shown at the bottom of each graph. The graphs are organised by the magnitude of impact on outdoor usage, as shown by the differences in scale along the x-axis.

The features shown in Figure 5 were found to increase outdoor usage up to two times; those in Figure 6 increased outdoor usage up to 3.5 times; and the features in Figure 7 had an even stronger impact on outdoor usage. In addition to the features reported here, several others increased outdoor usage to a lesser extent.

Discussion

These results show that several environmental features are strongly linked to levels of outdoor usage at assisted-living facilities. While a significance level of 0.10 was used to develop the statistical model, when the analysis was complete, the features presented here were all significant at the 0.01 level.

In addition to being highly significant, the magnitude of these effects is quite large. For example, Figure 5 shows that the feature with lowest impact (3-5: ‘the outdoors can be reached entirely by paved walkways’) still increases the amount of time spent outdoors substantially – by an additional 51 minutes per week. Anyone working with older adults in residential care settings knows the difficulty of influencing habits such as outdoor usage or physical activity, and this would be a substantial increase.

The environmental feature with the highest impact (item 6-8 in Figure 7: ‘the outdoor area has good views of birds and wildlife’) is associated with a nearly 10-fold increase in outdoor usage – from 118 minutes per week to 1,032 minutes per week. This is the equivalent of going from about 27 minutes per day to nearly two and a half hours per day, which is a radical change. As a statistical projection with all other variables held constant, this does not necessarily reflect what would happen in actual experience, with multiple variables operating in each case.

Nonetheless, these results suggest that the physical environment can have a significant and powerful effect on outdoor usage in long-term care settings.

Overall, the findings strongly supported the main environmental concepts found in the published literature on this topic, which is based more on practical experience than on quantifiable research. By incorporating these prevailing concepts as hypotheses, this study provides confirmation that specific environmental features do influence the behaviour of elderly residents. Generally, the main types of features that have long been considered important by practitioners, such as safe paving, good seating and strong indoor-outdoor connections, were also found to be important in this study. Several specific features thought to be important were not found to be significant here, possibly due to correlations among similar features.

There were several features that showed counter-intuitive or insignificant results in this study, primarily due to correlations among similar environmental features. Environmental features are often found to be associated with each other19, leading to multicollinearity problems during the statistical analysis and, therefore, possibly cancelling each other out in the model. This paper focused on the positive correlates of outdoor usage only, but future papers and follow-up studies are needed to disentangle the complex relationships among the environmental variables.

In addition, self-selection may have introduced bias, if the people agreeing to participate were the most active and outgoing residents. However, it is also possible that the participants self-selected from the most available and ‘housebound’ residents, while more active residents were off site or busy with other activities. To overcome possible bias, future studies could develop a strategy for randomly selecting participants. Past studies by this research team were unable to recruit sufficient numbers by this process and encountered resistance to this approach on the part of facility administrators.

There are several ways in which future studies could examine and build upon this study to triangulate and confirm or question the findings presented here. These include:

a) Behaviour-mapping: add an observational component at selected sample facilities, such as those with the lowest and/or highest environmental ratings;

b) Interview: add a structured interview component to obtain more in-depth understanding of how specific components of these environmental features influence residents’ behaviour;

c) Interaction: further analyse how different environmental features interact with each other (for example, are some features effective only in the presence of others?); and

d) Intervention: conduct an intervention study to test some of the environmental features in actual settings.

Conclusion

Implications for theory and literature. This study helps fill a gap in the existing evidence base on how the physical environment impacts on outdoor usage in residential care settings. Although there is rapidly growing interest in the importance of this topic, there is still comparatively little quantifiable research. Having a greater number of robust studies will make it easier to compare results and develop further theories to explain environmental influence on the behaviour of older adults, not only in regard to outdoor usage but also, by extension, in regard to other environment-behaviour issues.

Implications for practice. Architects and landscape architects can benefit from having information on environmental features that support resident usage of outdoor areas. These findings can also be useful in convincing decision-makers to budget outdoor improvements at existing communities, or to include this as a serious consideration in planning new communities.

The environmental audit tool used in this study will be adjusted based on the findings and released for use in evaluating existing communities or planning new ones. The basic design principles have been incorporated in a DVD-based educational programme, certified by the American Institute of Architects for continuing education credit20. Although this study was conducted in assisted-living settings, many of the concepts may apply to other levels of care, such as nursing facilities, senior apartments and CCRCs (continuing care retirement communities).

Cost-effectiveness. By providing information on the relative role of different environmental features, this study will make it easier for administrators to make informed decisions when allocating scarce budget resources. For example, some changes may be quite feasible and inexpensive, compared with the magnitude of their effect

on resident behaviour.

Overall, environmental improvements have the advantage of being relatively permanent and cost-effective after initial investments are made. Unlike programmed activities that require the ongoing expenditure of funds and availability of staff members to provide continuing services, the environment can provide health-promoting opportunities day after day, year after year, at the cost of basic upkeep and maintenance. In spite of diminishing resources and a growing population of older adults, it may be possible to significantly improve the health and quality of life in residential care settings, by improving access to nature and the outdoors through environmental design.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by SBIR grant No. R44AG24786 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), a division of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Statistical analysis was provided by Matthew Cefalu and May Boggess at the Department of Statistics, Texas A&M University.

The research design received valuable input from Roger Ulrich, Department of Architecture, Texas A&M University. Many thanks to the assisted-living facilities, residents and staff members who participated in this study, and to Ronald L Skaggs, FAIA, for his generous support and encouragement.

Authors

Susan Rodiek, PhD, NCARB is a Ronald L Skaggs endowed professor of health facilities design at the Department of Architecture, Texas A&M University

Chanam Lee, PhD, MLA is associate professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, Texas A&M University

References

1. Connell BR, Sanford JA, Lewis D. Therapeutic Effects of an Outdoor Activity Program on Nursing Home Residents with Dementia. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2007; 21(3/4):195-209.

2. Fujita K, Fujiwara Y, Chaves P, Motohashi Y, Shinkai S. Frequency of going outdoors as a good predictor for incident disability of physical function as well as disability recovery in community-dwelling older adults in rural Japan. Journal of Epidemiology 2006; 16(6):261-270.

3. Jacobs J, Cohen A, Hammerman-Rozenberg R, Azoulay D, Maaravi Y, Stessman J. Going outdoors daily predicts long-term functional and health benefits among ambulatory older people. Journal of Aging and Health 2008; 20(3):259-272.

4. Takano T, Nakamura K, Watanabe M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2002; 56(12):913-918.

5. Cutler LJ, Kane RA. As great as all outdoors: A study of outdoor spaces as a neglected resource for nursing home residents. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), The role of the outdoors in residential environments for aging (pp29-48). New York: The Haworth Press; 2005.

6. Cranz G, Young C. The role of design in inhibiting or promoting use of common open space: The case of Redwood Gardens, Berkeley, CA. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2005; 19(3/4):71-93.

7. Rodiek S. A missing link: Can enhanced outdoor space improve seniors housing? Seniors Housing and Care Journal 2006; 14:3-19.

8. Joseph A, Zimring C, Harris-Kojetin L, Kiefer K. Presence and visibility of outdoor and indoor physical activity features and participation in physical activity among older adults in retirement communities. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), The role of the outdoors in residential environments for aging (pp141-165). New York: The Haworth Press; 2005.

9. Michael YL, Green MK, Farquhar SA. Neighborhood design and active aging. Health and Place 2006; 12:734-740.

10. Berentsen VD, Grefsrod E, Eek A. Gardens for people with dementia: Design and use. Tonsberg, Norway: Ageing and Health, Norwegian Centre for Research, Education, and Service Development; 2009. Available at www.nordemens.no/?pageID=138

11. Cooper Marcus C. Alzheimer’s garden audit tool. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), Outdoor environments for people with dementia (pp179-191). New York: The Haworth Press; 2007.

12. Grant CF, Wineman JD. The garden-use model – An environmental tool for increasing the use of outdoor space by residents with dementia in long-term care facilities. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), Outdoor environments for people with dementia (pp89-115). New York: The Haworth Press; 2007.

13. Regnier V. Design for assisted living: Guidelines for housing the physically and mentally frail. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2002.

14. Zeisel J. I’m Still Here: A breakthrough approach to understanding someone living with Alzheimer’s. New York: Penguin; 2009.

15. Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. Visits to an outdoor garden: Impact on behavior and mood of nursing home residents who pace. In B J Vellas, G Fitten & G Frisconi (eds), Research and practice in Alzheimer’s disease intervention in gerontology (pp419-436). Paris: Serdi Publishing; 1998.

16. Mooney P, Nicell PL. The importance of exterior environment for Alzheimer residents: Effective care and risk management. Healthcare Management Forum 1992; 5:23-29.

17. Lang R, Dhavale D. Beyond megalopolis: Exploring America’s new “megapolitan” geography. Metropolitan Institute Census Report 05:01; 2005. Accessed 5 February 2007 from www.mi.vt.edu

18. Fovell R, Fovell M. Climate Zones of the Conterminous United States Defined Using Cluster Analysis. Journal of Climate 1993; 6:2103-2135.

19. Lee C, Moudon A. The 3Ds+R: Quantifying land use and urban form correlates of walking. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2006; 11(3):204-215.

20. Rodiek S. Access to Nature for Older Adults. Threepart DVD series; 2009. Available from Center for Health Systems & Design, www.accesstonature.org

|

1.1.jpg)

|